What Can Result When Attempting To Draw Back A Bow That Has Too Much Draw Weight?

Innovation |

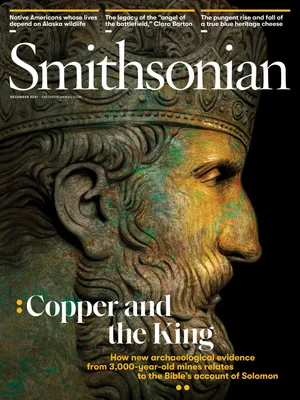

The Quest to Shoot an Arrow Farther Than Anyone Has Before

In indomitable pursuit of an exotic earth record, an engineer heads to the desert with archery equipment you lot tin can't get at a sporting goods store

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/21/5d/215d750e-67aa-4857-987d-c1089c44a8f3/dec2021_g11_archery.jpg)

Poised on a Nevada salt flat, Alan Example, 1 of the world's top practitioners of flight shooting, aims his custom-built bow, which requires so much strength to describe he must use his legs.

Erin TriebPhotographs by Erin Trieb

In an ancient white common salt flat, 30 miles southward of Nevada's Route 50—"The Loneliest Road in America"—a human being is looking up into a blue sky. His head is wrapped in a makeshift keffiyeh scarf to protect him from the dominicus. In a few moments he will lie down on his back. Between his upraised legs he volition cradle a contraption akin to a medieval crossbow, and point information technology at an angle of roughly forty degrees in the direction of a hazy mountaintop some four miles abroad. He is preparing to shoot arrows out into the thin desert air, one of which he hopes will break archery'south worldwide altitude record of ii,028 yards, or 268 yards across the ane-mile marker.

"This is virtually to get interesting," he says with a nervous laugh. Alan Case, a bemused engineer and designer from Beaverton, Oregon, has spent the by 15 years chasing that distance tape, which was set in 1971 by an archer named Harry Drake. The champion used a muscle-powered device chosen a footbow, similar to the i Case is warming upwardly with this forenoon vi,100 feet above ocean level at Smith Creek Dry Lake. It is near 50 years to the mean solar day that Drake ready the record. At 55 years erstwhile, Example is Drake'south historic period at the fourth dimension. "Later near four or five do shots I start to have fun," Case says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/51/72/517214dd-a333-46b7-baff-7225f92ff645/dec2021_g12_archery.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b8/b9/b8b921b4-a03e-47f7-a6be-44fc1134cadb/dec2021_g14_archery.jpg)

Despite the oestrus, one might assume that archery fans would be thronging to the desert to witness such a milestone. Yet there are no crowds. Footbow archery, or "flight shooting" or "flight archery," has no following. Once pop, distance shooting in America waned when it was believed that an arrow had been shot as far as information technology could go. A handful of archers around the world, though, imagined there might nevertheless be records to gear up. But where practise yous detect a space wide and empty enough to practise and compete? Beaches are windy and ofttimes full of people. Arrows get lost in flora-filled parks—also full of people. In the United Kingdom, they've tried competing on airfields.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/da/e5/dae52308-4ca2-4ea9-b262-7ff2aa500d66/dec2021_g22_archery.jpg)

In that location's another reason for the lack of popularity: the equipment. You can't only purchase a footbow at a sporting goods shop. Edifice your own and tuning it precisely is onerous. "This guy is unbelievably committed to getting this done," says James Martin, standing alongside a worktable Case has prepare side by side to his minivan on the flats. "It's amazing. He works twelvemonth-round every evening computer-modeling means to go more free energy into the pointer."

Within Case'southward van are tools, spare parts, a sleeping pocketbook, food wrappers and his family domestic dog, Buddy. Roughly 15 friends and family members have caravanned here to erect a pop-upwardly tent amidst the alkaline hummocks and spiny shrubs. They are also putting in identify an electronic altitude-measuring device of the type highway surveyors use. It will compute the winning shot to within one centimeter from the firing line over a mile away.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/b8/8db84786-331a-4b81-9b62-ca703fd75690/dec2021_g04_archery.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/db/94/db94976b-c4e3-4f0d-b285-a5eaf4859f06/dec2021_g06_archery.jpg)

The gregarious Martin, a physicist at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico, is likewise a distance shooter, and holds records using specialized difficult-to-draw bows fabricated for him past Example. Similar many archers, he has a os-burdensome handshake. He is something of a Boswell to the reserved Instance whom he has known for several years.

To shoot an arrow the length of more than than 20 football fields defies traditional notions of archery, says Martin, first a staccato tutorial. "What is a bow? There's the longbow like the English language used to shoot, a D-shaped design, very elementary affair. Those shoot the least far. Then there are recurve bows with curved tips that create more energy than the longbow. Those shoot farther and so that's another category. Last are compound bows. Those have confusing-looking pulleys and multiple cables."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/96/c396f6ab-7d56-459b-870f-0d6f622cb308/dec2021_g05_archery.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fd/e4/fde44d8f-72f3-47b3-ab4a-f0966343e5bf/dec2021_g02_archery.jpg)

He continues. "Bows are classified past how hard they are to draw back. So if information technology takes 35 pounds of force to pull information technology back, that's a 35 draw-weight bow—or 35 weight class. Then in that location's a fifty-pound form and a 70-pound class—seventy pounds of draw weight would exist a very heavy hunting bow. People chase grizzly bears with them. Concluding is the unlimited class where anything goes. The near extreme stuff. That's what we practice and why we're hither today."

Instance'southward footbow is not only the hardest to shoot, but also the most unpredictable and dangerous. It requires an archer to place his feet in stirrups and push outward with his legs while straining to pull dorsum on the bowstring with his hands, creating a draw weight of up to 325 pounds. That's a tremendous amount of brute force to launch an arrow that weighs fiddling more than a couple of pencils at upward to 800 anxiety per second, roughly the same speed every bit a .45-quotient bullet.

If a bow limb breaks—he has broken more than xl of them—the entire apparatus seeks the quickest style to dissipate its tremendous free energy. Archers call information technology "blowing up."

"I've had some mishaps with the bow," says Example. Actually, he clarifies, "a whole lot of mishaps. Information technology plays in the mind a scrap."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/51/1a/511a215f-602e-47a3-bc5f-439747781ff1/dec2021_g17_archery.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/80/a0/80a07227-cc79-47a4-8d5e-08cd9bec864b/dec2021_g20_archery.jpg)

Footbow "arrows" are perhaps the virtually fickle variables in a long shot, and they compound the sport's danger. Example produces a metal coffer he calls his "jewel box." Inside are perhaps 20 arrows of various lengths—as short as 8 inches, not longer than 13 inches—some for practice, some for competition. They announced quite different from the Paiute Indian arrows that Pony Express riders once dodged along the nearby mail trail in the 1860s. These resemble slender knitting needles.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/29/fd/29fde156-cb8c-444b-89ec-d515055209f1/dec2021_g19_archery.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/75/47/754796d2-a702-48a8-b5be-820ff845a1fd/dec2021_g18_archery.jpg)

To build one, Case starts out with an ultralight carbon fiber rod and carefully fashions it into a streamlined shape, often using model rocketry software as a guide. He so applies a stainless steel tip and a nock, the grooved stop that fits on the bowstring. A series number is etched on each shaft. Instead of feathers, the traditional fletching at the rear end of an pointer, Case uses fragments from a safety razor blade. "The blades are difficult to notice," he says. Longer arrows are more than forgiving than shorter, merely neither is dependably stable, and if one goes amiss on launch information technology tin can come back at the archer with a vengeance.

This forenoon, Instance has been shooting exercise arrows, pulling the bowstring back little by picayune, limbering up for the big shot that will occur in the cooler evening. He is confident, partly because he's certain he has already beaten the record, just not to the satisfaction of the official USA Archery rules book.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/c7/33c78123-60c7-4057-bec0-204b51bdaf95/arrow_triptych.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2c/07/2c0763a9-10a8-476b-a756-05561123a84d/dec2021_g15_archery.jpg)

The competition today is a solo affair—Instance versus history, with no other competitor or official on hand to witness the feat, which is supposed to be documented and attested to by Case and his retinue. The but person who can psyche him out before the official shot is himself. I enquire Instance if he ever gets the yips—a subtle simply disabling mental assail that afflicts golfers when they putt. "If I recollect most information technology too much I get nervous," he says. "It'south weird. [Archers] sometimes develop something called target panic. It starts when they maybe call up too much about hit the target, and the pressure. It builds upward and information technology gets then bad sometimes they just get-go to pull and they let go. It takes years sometimes to get over it. I try to think differently. If I but tell myself it's my job, I'll do okay."

Case decides to take another practice shot, increasing the pull weight. Shortly some members of the caravan will drive out and brainstorm looking for his arrows. Finding an eight-inch black carbon rod confronting the white flats and a backdrop of shimmering mirages is nearly impossible for the untrained middle. "You accept to know how to look for an arrow," says Martin. "It hasn't gone anywhere. It'due south out at that place."

In the merciless heat, Instance lies down on his shooting blanket. The wind cups of his portable weather condition station are nearly nevertheless, although dust devils are visible in the distant west. The onlookers, their legs and shoes covered in white dust, terminate what they are doing and fall silent. He pushes outward on the bow with his feet, struggling to aim, strains to pull back on the bowstring, and then releases.

It is perhaps best that the archer's next utterance exist forever lost on the desert wind, but it consists of equal parts pain, surprise and intense anger. In a split 2d his arrow has bored itself deep into the height of his right foot and shattered a bone. He reaches down and pulls out the carbon rod, and with it comes a blitz of blood. Alan Instance's quest for the official title is ended, for now.

Bulls buck cowboys. Mountaineers miss handholds. Surfers wipe out. The next morn I visit Example in his pocket-sized room at the Cozy Mountain Cabin in nearby—by Nevada standards—Austin (popular. 113). Doctors 111 miles abroad in Fallon had patched him up. His new crutches lean in the corner and his foot is elevated. He is surprisingly good-natured.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/40/7c401879-9797-4e20-b303-fff57b6a9869/quad-1.jpg)

Erin Trieb (3); 10-ray courtesy of Alan Case

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/96/f6/96f60899-c826-4268-a2d9-c0f550990deb/dec2021_g13_archery.jpg)

"I don't know what happened," he says. "It'southward crazy. I was starting to experience good. Simply keeping it on the target." Always the scientist, he calculates that the unabridged incident probably lasted no more than 0.005 of a second. "It doesn't take much to deflect an pointer, but information technology takes a lot to end ane caput-on."

He vows to be back. I remind him of a historical fact he already knows well: The last great culture to prize long-distance archers were the Turks in the get-go of the 15th century. Some of the best were said to reach shots upwards to 900 yards. The near revered champions earned mezils, elaborate rock monuments memorializing their winning shots.

In that location's picayune dubiety Instance will earn his mezil, even if it's only a line in a record volume; the caravanners found one of his exercise arrows at over a mile. Next flavour the humidity volition once again be low in the desert, the winds notwithstanding and the salt flats porous plenty to plant arrows. For now, Harry Drake's record stands. It hasn't gone anywhere. It's out there.

*Editor's Note, 11/22/2021: A explanation in an earlier version of this story misidentified Alan Example's wife. She is Adrienne Lorimor-Instance.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/quest-shoot-arrow-farther-anyone-has-before-180979009/

Posted by: hughesthind1949.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Can Result When Attempting To Draw Back A Bow That Has Too Much Draw Weight?"

Post a Comment